|

|

||||

|

|

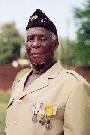

by Donald Levit  Little gems from the Third World float westward once in a while, under- promoted/distributed for limited runs, or remora-like hitch a ride on bigger fish, like contributions to the omnibus 11’09”01 (September 11). The exception, of course, was The Gods Must Be Crazy, from Among current smaller fry is director-writer Kollo Daniel Sanou’s Tasuma, The Fighter, Burkina Faso’s domestic champion and the first-ever African movie released simultaneously “on the [home] Continent and in the USA!” In common with others of its kind, this charmer overlays a wry sense of life’s contradictions, as gentle unsophisticated (in Western terms) peoples confront the incomprehensible muddle of post-colonial culture. The central character is Sogo Sanon (Mamadou Zerbo), nicknamed Tasuma, subtitled le feu on-screen, literally “fire,” but better rendered “fire-eater,” “-brand” or “-ball,” for his daring in the tiralleurs senegalais, black troops who fought for mother France in Indochina and Algeria. Mustered out in 1962, he has for years awaited pension payments that did not become available until later and, a fortune to him, are infinitely less than those given white ex-combatants. With national troops on shooting maneuvers near his bare subsistence-farming village, he finds and keeps a stray grenade and, in uniform, bicycles to larger Bobo (-Dioulasso) for a first payment. Bureaucratic wheels grind slowly if at all in Sogo goes back to the provincial capital, and again . . . and again, but while some other veterans collect, his name has been confused, the identification number does not jibe, officials and clerks are patronizing, Khalil shows up to foreclose, and Sogo returns to town with an antiquated unloaded carbine. As Sogo’s praises are recounted in song -- the words are organic, unlike the chorus interludes of Cat Ballou or narration sung against “primitive” drawings in As in the guppy world, the males appear dun, often in mothballed uniform, while their womenfolk shine in bright patterned robes and headgear even at work. And work they do. Man’s work entails lazing around philosophizing over tobacco pipes, giving away daughters in marriage, and playing at bureaucrats and soldiers; the females do everything else, besides being more practical and having to teach their partners honesty and horse sense. It is they, too, who take matters into their hands to break up the logjam. The national constitution of 1991 recognizes and protects “the rights (namely the economic rights) of women: right to choose one’s bridegroom, ban of sexual mutilations, economic rights: Women’s Bank.” There is no flashy stuff, no angles, not even an overhead. Half-mad former schoolteacher Doba (Serges Henri) runs around snapping photos everywhere; one suspects his blue plastic camera contains no film, and it would be no surprise to learn that Tasuma was made with one 35 mm camera. With no (physically) beautiful people or easy big sky and landscapes, but only the barest of locations, the movie is a delightful dry comment on human beings, integrity and relationships. Following the People’s Democratic Revolution, in 1984 (Released by Art/Mattan Productions; not rated by MPAA.) |

||

|

© 2024 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |