|

|

||||

|

|

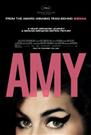

by Donald Levit  Turn Turn Turn. Nina Simone and Amy Winehouse are coming (back) even more into their own, first of all for their outstanding talents. Second, for troubled love lives. Third, for alcohol (and other substances) abuse that, among other things, made performances and even appearances problematical. Five years ago in a film by ex-husband and manager Andy Stroud and in coincidentally current documentaries by Jeff L. Lieberman and Liz Garbus, the High Priestess of Soul mesmerizes with her music as well as uncompromising political stance, racial rage and psychological problems. And, like her, self-sabotaging a brilliant future, the Russian Jewish girl from North London has her own two non-fictions. Before the beginning of the early end as a member of the 27 Club, she was simple, girlish, happy and heartbreakingly wonderful in an a-ha moment on the intimate 2006 stage that was her true métier in Amy Winehouse: the day She came to Dingle. The talent that Tony Bennett classed with those of Billie and Ella is on show again, later and shadowed, in Asif Kapadia’s Cannes- and Edinburgh-lauded and Film Society of Lincoln Center sneak-premièred Amy, two hours and eight minutes itself awash in controversy little less than its subject was. Complimented on not sounding like an elocution-class graduate, (despite the documentary’s title) unlike ubiquitous single-name celebrities, retro yet ahead of the styles, she is shown as having the instinctive courage to be herself. Trouble was, like Marilyn Monroe, she never came to define exactly who that self was amidst the burden of fame once “they set you on a treadmill.” The on-screen emphasis on media feeding frenzy, flashing cameras, and fickle fans is ham-handed although an accurate reflection of the limelight that at least contributed to her death, poisoned by the alcohol that doctors warned her against, on top of bulimia and heavy heroin and crack cocaine abuse. Along with interviews and/or voiceovers from family, child- and adult-hood friends, associates, bodyguards, hangers-on, exploiters and enablers, there is killer performance and studio footage and home movie material of her as a child and teenager. Her accent is so thick, sometimes even to lyrics, that English-to-English sub-titles and cursive side-titles are welcome. Too, there are hundreds of double-imaged lines of her early and late handwritten poetry-songs. Access to such personal documentation had been granted by the immediate family, some of whom were later to repent, feeling uncomfortable about aspects presented of their Amy’s life. Along with the massive eyeliner copied from cubanas in Miami, Ronettes beehive hairdo, short shorts and flats, there comes the proliferation of body tattoos, of particular significance a prominent “Daddy’s Girl” sandwiched between a horseshoe and sexy pinup. Taxi driver “jazz vocalist” Mitch Winehouse has been most vociferous in objecting to this “preposterous” portrayal of his daughter, and most public in the aftermath. In the film young Amy claims to be happy when unfaithful he left her and younger Alex with their mother Janis, who was not strong enough to control the girl’s smoking weed and raising hell. Mitch claims that this record concentrates on the negative and, in his own case, misleads about parental exploitation or at best lack of good judgement. While she comes across as sad, smart money says that what upsets him is that he comes across as bad. Given Amy’s pathetic clinging to no-goodnik druggie husband Blake Fielder-Civil (who introduced her to hard drugs and smuggled heroin into her rehab), it is apparent that, like other ill-fated singers (and women who are not), she had a serious problem with the men in her life. Deny it though Daddy may, in St. Lucia away from substance temptation, Amy grouses about his profiteering at the expense of her well-being and happiness. Whatever the root cause, she dotes on Mitch, who less that a year after her death rushed into print Amy, My Daughter. Many among those who knew this lost gifted waif knew where she was headed. It is part of the anguish that neither they nor she could change that. What remains is the beauty and -- unlike the life --unhistrionic artistry on recordings and in film. (Released by A24 and rated "R" for language and drug material.) |

||

|

© 2025 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |