|

|

||||

|

|

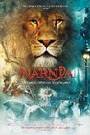

by John P. McCarthy  What to expect from this live-action adaptation of C.S. Lewis' Christian allegory? Imagine a movie that's one part Lord of the Rings, one part Finding Neverland, and one part Passion of the Christ and you'll have a pretty good idea. Those are five (counting the Rings trilogy) estimable films -- and The Chronicles of Narnia is formidable and frequently spellbinding -- but their strongest points don't necessarily constitute the overlap. Robust and well-acted, Narnia comes off as a sanguine, blustery adventure. There's a thematic rigidity that can be interpreted as a plus or a minus. Like the popular children's books penned by Oxford don Lewis, the movie taps into numerous traits of a certain Anglo-Saxon mindset. They include stout monarchism, militaristic fortitude, and a penchant for incorporating pagan symbols and talking animals into any entertainment. These qualities can be read as universal or specific to the English middle-class in the mid 20th-century and their historical circumstances. They can also be seen as virtues or failings. Courage and a willingness to fight those seeking to subjugate your island nation is an admirable stance. The British Empire's appetite for conquest draws on the same traits and isn't so laudable. And there's a tension between skepticism rooted in Britain's empirical, common sense intellectual tradition and the childlike openness to faith Lewis champions. While he admirably incorporated this into his writing, any subtlety is occluded on screen. The Peter Pan parallel mostly stems mainly from general plot similarities, although eternal youth and salvation have much in common. "We're not heroes; we're from Finchley," declares one of the four Pevensie children, evacuees from the London suburb sent to a professor's rambling country house to escape the Blitz. Brave little Lucy (Georgie Henley) discovers the wardrobe during a rainy day game of hide-and-seek. Stumbling into a winter wonderland, she encounters Mr. Tumnus, a half-man half-deer creature who resists the order (or is it an urge?) to abduct the little girl. She represents innocence (some may call it gullibility), a state Lewis and any advocate of organized religion doesn't want us to outgrow. Black sheep Edmund (Skandar Keynes) is the next to travel into the fantasy land, where he promptly meets Narnia's ruler the White Witch (played by a wickedly icy Tilda Swinton.) She enlists him to betray his siblings, knowing the children are destined to fulfill a prophecy that says two sons of Adam and two daughters of Eve will restore order to the realm, now a totalitarian state where "deep magic" is rejected, citizens are persecuted and Christmas never comes despite the perpetual winter. Once the older children Susan (Anna Popplewell) and Peter (William Moseley) arrive, two beavers with cockney accents take them to Aslan the lion, leader of the exiled forces of good. A wise general, Aslan, (voiced by Liam Neeson), directs the children in their fight against the Witch and her menagerie of mutants and cretins. The story's zoological demarcation feeds into its topicality. For example, the Witch's henchmen are German Shepherds (Nazis) -- or they could be the Russians of the Cold War or secular foes of religion in today's culture wars. Lines such as "I believe in a free Narnia" could even come from a speech by America’s current Commander-in-Chief. All talk and academic debates are left behind fairly quickly. Belief is one thing. Acting on those beliefs is all-important. The allegory becomes obvious if not ham-fisted when Aslan sacrifices his life for Edmund (a marginally culpable Judas). This ripe sequence will remind viewers of Passion of the Christ. Whereas Gibson stopped at the crucifixion, Lewis rolled deeper into the New Testament by depicting a resurrection, with Susan and Lucy as Mary and Mary Magdalene figures. All this is a preamble to a fierce battle led by Peter against the evil witch and then the crowning of the four victorious children as stalwart monarchs of the realm. Comparisons with Lord of the Rings are most obvious during the battle scenes, yet from a production point of view Narnia is not possible without that trilogy. Also filmed in New Zealand, it shares locales and an overall look. Toddlers in the audience may cower at certain points. If the lesson that salvation is not for the faint-hearted registers, they might try to disguise their fear. The lack of nuance in The Chronicles of Narnia is part of its appeal, even if it causes skeptical adults to groan. Christian fundamentalists will love it. They might even absolve helmer Andrew Adamson of indecency for directing the Shrek movies. (Released by Buena Vista Pictures and rated "PG" for battle sequences and frightening moments.) |

||

|

© 2026 - ReelTalk Movie Reviews Website designed by Dot Pitch Studios, LLC |